Read stories from farmers all around the world and why they chose T-L.

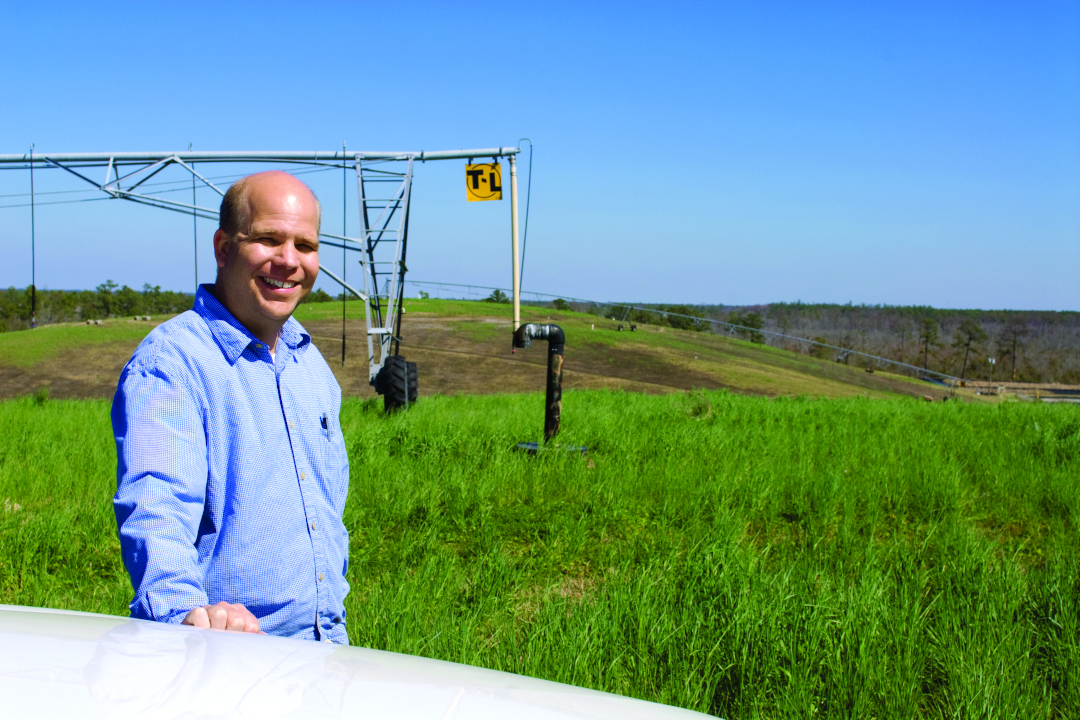

Samuel P. Hawes IV

"We've been happy with our T-L pivot systems. There have been no problems at all with them unless you count a tornado flipping one over, however, our dealer was quick to get here and get it running again."

Samuel P. Hawes IV refers to it as a “partnership” of sorts that makes their system the “ultimate type of treatment” for a landfill. Sam is the manager of the New Hanover County Landfill at Wilmington, North Carolina.

You might not think of landfill operation as exciting, but, that’s not the case when it’s utilizing advanced technology that wins national awards, international attention, and visits from interested officials from as far away as India and Thailand.

Landfill operators almost everywhere are looking for low cost, alternative treatment systems versus conventional treatment methods. New Hanover’s truly cutting edge technology “partnership” landfill system, according to Hawes, is one that effectively and efficiently marries wetlands with sprinkler irrigation.

When it rains, water percolates through the landfill waste and picks up contaminates called leachates. So, like any other wastewater, it has to be treated before it can be discharged to surface waters.

Historically, conventional wastewater treatment plants do this job but treating nitrogen, especially during the winter, can be a problem. Additionally, a licensed operator has been on duty five days a week, and there’s maintenance on the blower, samples must be taken and submitted to a laboratory for analysis—in short, the plant and its operation is expensive.

Five years ago landfill management decided to try something new in the hope of being able to reduce, and eventually eliminate, the discharge water.

First, rather than operating a waste treatment plant, the raw, untreated leachate is run through wetlands primary “filters”. When it leaves the wetlands the water is basically a low-grade liquid fertilizer.

Second, the landfill area is covered with a synthetic liner. After two feet of soil is placed on top, the grass is seeded to protect against erosion.

Next, a T-L center pivot was installed, through which the wastewater is applied at a rate such that the soil can assimilate the nutrients. Tests are made to ensure that all the wastewater can be handled without any runoff.

That was the plan, and, “It’s met our expectations,” Hawes reports. The first T-L pivot system covers ten wetted areas on what appears to be a rather steep, 98-foot high hill. A second T-L system put in last year covers a similar area on another man-made hill nearby.

“We’ve treated approximately seven million gallons of raw leachate with this system that otherwise would have had to be processed through a treatment plant,” Hawes observes. “The county expects significant cost savings in the future.”

“The nitrogen and phosphorous and whatever else was in the leachate would have still gone into the river. So, this is really also a water quality project helping to protect the fresh waters of North Carolina.”

He notes that estimated long term costs of this “partner” system versus conventional treatment will be quite a bit less, too.

At a rate, on average, of 650 tons of waste a day, it’s estimated that the entire landfill area will have another 25 to 30 years of life.

Once the landfill is closed it’s anticipated that it will be made into a park. A conventional treatment system doesn’t lend itself to this kind of conclusion due to costs, noise, and odors.

“We’ve been happy with our T-L pivot systems. There have been no problems at all with them unless you count a tornado flipping one over,” Hawes says. “However, our dealer was quick to get here and get it running again.”

“In fact,” he continues, “the reason we chose the T-L pivot over its competitors was the hydraulic design. We could also avoid most of the problems that electrically powered systems have with lightning strikes, a frequent occurrence at the landfill.”

“We plan to expand this concept as we close more current landfill sites. So,” Hawes says, “we’ll probably need at least two, maybe three more T-Ls. Once we get to that point we ought to be close to zero discharge into the river.”

- Products

- Center Pivot

- Crops

- Alfalfa/Hay

- States

- North Carolina

- Countries

- United States