Read stories from farmers all around the world and why they chose T-L.

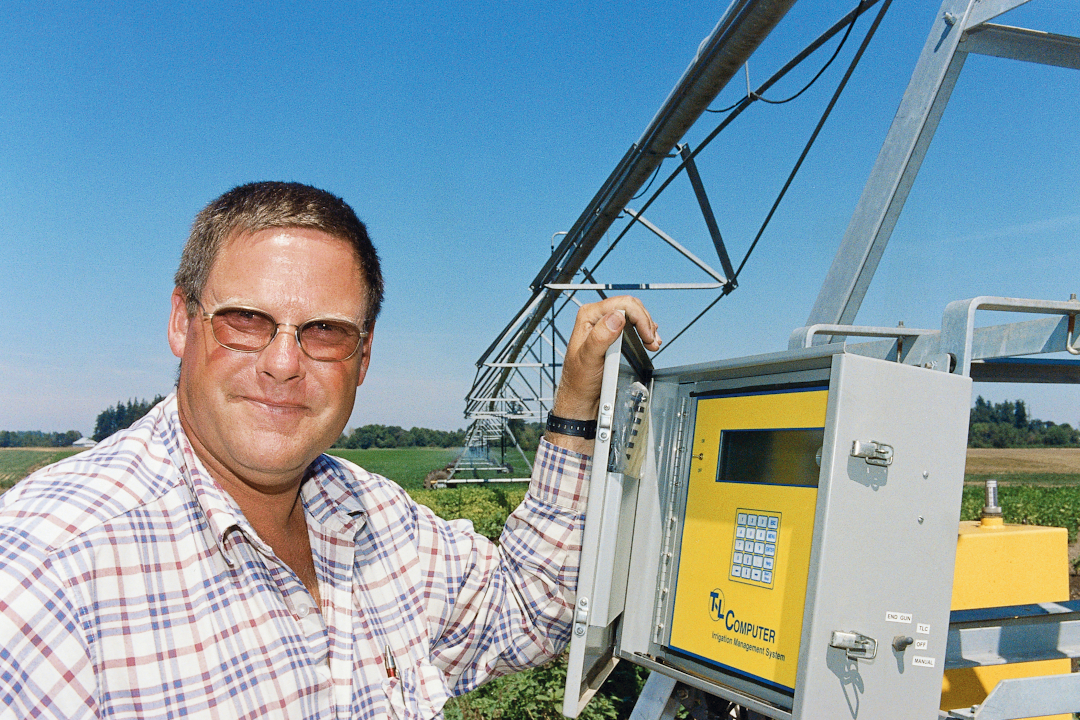

Larry Venell

"I really like the computer system on our newer T-L systems. We just program it, and the machine goes around doing its own thing. Then, when it's done, it stops and waits for us. Anything like this that saves labor is a big thing for us since we have a hard time finding good labor around here."

His parents started farming in 1956 near Corvallis, Oregon, with 165 acres. Today, after almost a half century of continual expansion, Larry Venell operates just short of 11,000 acres. This includes 8,500 acres devoted to producing grass seed for his own seed company and contract varieties for other companies.

Approximately 85 percent of this grass production is perennial ryegrass and tall fescues. His irrigation centers around eight T-L’s, some large mobile guns, and a couple of electric systems that came with a land purchase that he plans to update with T-L’s. Venell’s oldest T-L’s are approaching 15 years of age.

He waters with either a T-L center pivot or a linear system, depending on field shape, Venell says and, depending on the amount of rainfall received, he’ll apply anywhere from eight to 18 inches of water during the season.

“The irrigated grass just fills more seeds. In a typical year, our irrigated grass will show a significant yield boost,” he explains. “But, what irrigation really does is allow us to add diversity to our program; the ability to switch and change crops.”

After field burning was banned, it became more difficult to make the proper rotations, especially during an arid summer. Being able to apply irrigation water has allowed Venell to add different rotations. Also, rather than having to rely on rainfall to get a uniform sprout after applying herbicide, irrigation ensures he achieves better control of the weeds.

“I really like the computer system on our newer T-L systems. We just program it, and the machine goes around doing its own thing. Then, when it’s done, it stops and waits for us. Anything like this that saves labor is a big thing for us since we have a hard time finding good labor around here,” says Venell.

“Our linear T-L’s will easily pull more hose than an electric linear, and a quarter mile machine can water a quarter mile square field,” he adds.

“An electric system will spin out at the end of the run trying to pull that much hose. This means somebody has to be there more often than with a T-L.” Venell comments that he considers a T-L system to be “a pretty straight forward machine and its hydraulics are an easier drive to understand and superior to an electrical drive.”

Larry also mentions that, “if we have a problem with an electric, it’s pretty much hidden and more complex to get figured out.” He notes also that when an electric system motor goes down, the unit is usually stuck out in the middle of the field, requiring his packing a replacement motor and tools way out to it.

On the other hand, only lightning strikes seem able to stop his T-L’s. This generally means some new parts are needed for the computerized management system, however the system; can still be run manually.

Venell is a pilot with a runway close to his main buildings. He often flies over his fields to check them out from the higher vantage point. “When I fly around, I can see the ‘spoking’ effect of an electric system’s constant stopping and starting,” he advises. “I don’t have any way to quantify it, but this spoking probably affects our yields. This doesn’t happen with a T-L’s constant movement.”

- Products

- Center Pivot, Linear Pivot

- Crops

- Grass

- States

- Oregon

- Countries

- United States